Stress Reduction Theory: why looking at nature is beneficial to our mental and physical health

Nature can have a powerful effect on health and well-being, as well as cognitive performance. which is why many architects and designers employ biophilic design principles. In particular, building design that prioritize views of nature can help reduce stress for occupants.

The city: a source of constant stimulation and risks to our mental health

Today, more than 50% of the global population live in cities, and this figure is forecast to rise to over 70% by 2050. Yet numerous studies have revealed that cities are associated with increased risks of mental health issues in comparison to rural areas, including an almost 40% greater risk of depression, double the risk of schizophrenia, and a greater risk of anxiety, stress and isolation1.

One explanation for this is that we are rarely in a state of physical and psychological 'rest' in cities. We are usually surrounded by motion and continuously stimulated by sound, crowds, traffic, smells, lights, etc. When this is combined with pollution, commuting, potential crime, etc., the stress factors are manifold, leading to a growing number of chronic stress situations with a considerable impact on our health and well-being.

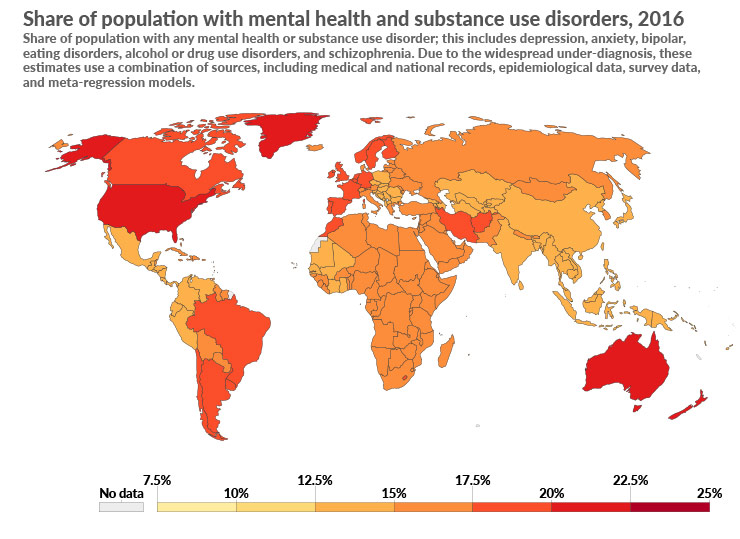

Today, 450 million people worldwide are affected by mental health issues2, costing the global economy $2.5 trillion3. This is considered one of the fundamental public health challenges we face this century.

Global map of population affected by mental health issues in 2016 (source: ourworldindata.org)

Workplaces: a source of stress and mental health issues

Mental health issues also affect a large proportion of employees in their workplace, specifically one in five workers, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Stress is one of the main issues identified and is known to be linked to cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, immunological and neurological diseases and disorders4. Issues such as workload, pressure from management, conflict with colleagues, uncertainty and a loud and uncomfortable working environment are all recognized sources of stress. The consequence: higher absentee rates and a significant decline in productivity. The economic impact on businesses is huge: losses of up to £15 billion every year in the U.K.5, and £79 billion in the U.S.6

Mental health issues at work in the media

Nature: A source of positive emotions and stress reduction

Certain environments can help us limit our exposure to stress and the associated mental and physical health risks: specifically, those found in nature.

In 1991, the researcher R. Ulrich developed Stress Reduction Theory (SRT), based on numerous studies, notably those carried out in hospital settings, to explain our emotional and physiological reactions in the presence of natural elements8.

This theory states that looking at scenery containing natural elements like greenery or water creates positive emotions and feelings like interest, pleasure, and calm, and has a restorative effect, easing our state of alert following a stressful situation. Our response is then improved rapidly and spontaneously9.

A theory confirmed by numerous studies

Belief in the restorative and therapeutic effect of nature in alleviating the harmful effects of the city goes back many centuries. As far back as ancient Rome, people noted that contact with nature could be beneficial in dealing with noise and urban congestion10. More recently, Ulrich’s theory has been supported by many empirical studies conducted on people in hospitals11, prisons12, residential communities13, offices14 and even schools15. The results demonstrated the beneficial effect of visual exposure to nature in the very short term on reducing blood pressure, heart rate, cortisol levels, sweating of the hands, muscle tension, etc. Positive psychological effects on mood, anxiety levels and feelings of comfort and relaxation were also measured and observed.

Effects closely linked to our evolution

The benefits of nature may be explained in the evolution of human kind, making Ulrich’s stress reduction theory what is also known as a ‘psycho-evolutionary’ theory.

For the majority of its existence, mankind lived outdoors. We moved into cities and inside buildings just a few centuries ago. As our bodies were unable to adapt to this new environment in such a short space of time, we are said to have maintained our inherent affinity towards nature (known as Biophilia ), as well as a predisposition to respond positively to natural environments. Looking at natural environments is said to inspire feelings of pleasure and calm in modern man, helping us block out negative emotions and distract ourselves from sources of everyday stress.

Savannah-type landscapes create positive and relaxing emotions due to our evolution

Conclusion: Prevent stress and mental health issues with views of nature from indoor spaces

In conclusion, it is now recognized, based on scientific proof, that living and working near green spaces, with views of water and plant life, may significantly help reduce stress and improve our quality of life and health.

If you live or work in a city, there are already tangible benefits to being around ponds, rivers, trees and plants, whether in parks, squares, gardens or paths, or even built into the roofs or façades of building17. And here’s the good news: as mentioned in the previous post on nature’s benefits for our attention span, inclusion of greenery and biodiversity is on the rise in new building and development planning, for environmental and public health-related reasons.

Inclusion of greenery and biodiversity is on the rise in new building and development planning

Over the past few decades, we have seen ‘therapeutic’ gardens springing up in healthcare establishments (particularly in the United States), with the aim of reducing anxiety, symptoms of depression and the need for pain relief, as well as improving patients’ quality of life and sleep. These gardens also enhance the experience and well-being of visitors and care staff. Residential properties with a view of nature are generally in high demand and cost more19. This is also true in the hospitality industry, where hotel rooms with a sea view, for instance, are the most expensive20. Biophilic design is increasingly used in office buildings to maximize outdoor views from workstations and incorporate indoor gardens and plant walls, both strategies to promote well-being, satisfaction and productivity21.

In all these instances, windows are key to giving occupants a pleasant and continuous visual connection to nature from indoors (where, it must be noted, we spend 90% of our time), facilitating recovery from stress. At the same time, they also let in natural light, which, in regulating our biological clock, also has a therapeutic benefit. At the same time, it's important to control this light, in order to avoid glare and uncomfortable temperatures.

Vast views through the windows allow a continual connection, facilitating recovery from stress

- Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, Kluge U, Galea S, Heinz A: Cities and mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017; 114: 121 DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121

- Investing in Mental Health, World Health Organization

- S. Trautman et al, The economic costs of mental disorders. Do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders?

- K. Nilsson, M. Sangster, C. Gallis, T. Hartig, S. de Vries, K. Seeland, et al. (Eds.), Forest, trees and human health, Springer Science +Business Media (2011), pp. 1-19

- At a tipping point? Workplace mental health and wellbeing, March 2017, Deloitte

- U.S. Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health, 1999

- Magdalena M.H.E. van den Berg et al, Autonomic Nervous System Responses to Viewing Green and Built Settings: Differentiating Between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Activity, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12(12), 15860-15874;

- R.S. Ulrich, R.F. Simons, B.D. Losito, E. Fiorito, M.A. Miles, M. Zelson Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11 (1991), pp. 201-230

- R.S. Ulrich, Aesthetic and affective response to natural environments, In I. Altman & J. Wohlwill (Eds.), Human Behavior and Environment, Vo1.6: Behavior and Natural Environment, New York: Plenum, 85-1 25

- Wolf, K.L., S. Krueger, and M.A. Rozance. 2014 Stress, Wellness & Physiology - A Literature Review. In: Green Cities: Good Health (www.greenhealth.washington.edu). College of the Environment, University of Washington.

- R.S. Ulrich, View through a window may influence recovery from surgery, Science, 224 (1984), pp. 420-421

- E.O. Moore (1982) A prison environment’s effect on health care service demands. Journal of Environmental Systems, 11, 17-34

- Ward Thompson C, Roe J, Aspinall P, Mitchell R, Clow A, Miller D (2012) More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc Urban Plan 105:221–229

- W.S. Shin, The influence of forest view through a window on job satisfaction and job stress, Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 2007; 22: 248253

- Ulrich, R.S. 1979 Visual landscapes and psychological well-being. Landscape Res. 0.44-23

- Orians GH, Heerwagen JH (1992) Evolved responses to landscapes. In Barkow JH, Cosmides L, Tooby J eds. The adapted mind: evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 555 -579

- Stigsdotter, Ulrika. (2019). Urban Green Spaces: promoting health through city planning

- C.C. Marcus, Healing Gardens in Hospitals, Volume I, Issue I: Design and Health, January, 2007.

- R. Kaplan, The Nature of the View from Home: Psychological Benefits, Environment and Behavior, 2001.

- Human Spaces 2.0: Biophilic Design in Hospitality

- K. Gilchrist et al. Workplace settings and wellbeing: Greenspace use and views contribute to employee wellbeing at peri-urban business sites / Landscape and Urban Planning 138 (2015) 32–40