Is the world facing a “looming cold crunch”?

Last October, I moved into a new apartment and it’s really, really hot. Being very sensitive to cold, I was thrilled to be able to walk around all winter in a T-shirt without ever getting cold. However, I dread the arrival of summer, with heatwaves becoming increasingly frequent. I could close my blinds during the day, but I don’t want to spend my summer vacation shut in a basement. So maybe I should invest in an air conditioner? But from an environmental and economic perspective, that really wouldn’t be ideal. It’s a tough decision… Yet some people wouldn’t think twice about opting for air conditioning. If you lived in Dubai or Hong Kong, you probably wouldn’t bat an eye! And that’s how we end up in a situation where air conditioning is causing global demand for electricity skyrocket.

Rise in global demand for air conditioning: the figures

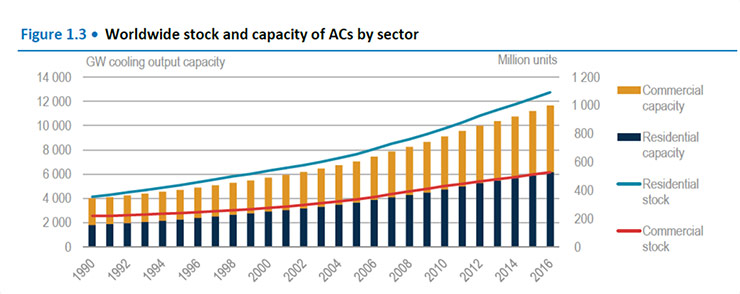

A recent report by the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction1 highlighted a clear rise in energy demand associated with air conditioning. The energy we consume when cooling our spaces has in fact already risen by 25% since 2010, and the world’s buildings are now equipped with more than 1.6 billion air conditioners (of which half are found in China and the US). However, the markets that now consume the most are not the world’s hottest countries: in places with daily temperatures above 25°C, only 8% of the population has an air conditioner!

The number of air conditioners worldwide is increasing dramatically (source: International Energy Agency)

According to the International Energy Agency2, energy consumption associated with air conditioning now constitutes 20% of all of the world’s electricity consumption in buildings. It has also risen more rapidly than all other categories of consumption (heating, lighting etc.). If we do not take action, this consumption could double or even triple in the decades to come, rendering air conditioning responsible for 40% of the increase in electricity consumption in buildings.

Serious consequences for electricity grids and carbon emissions

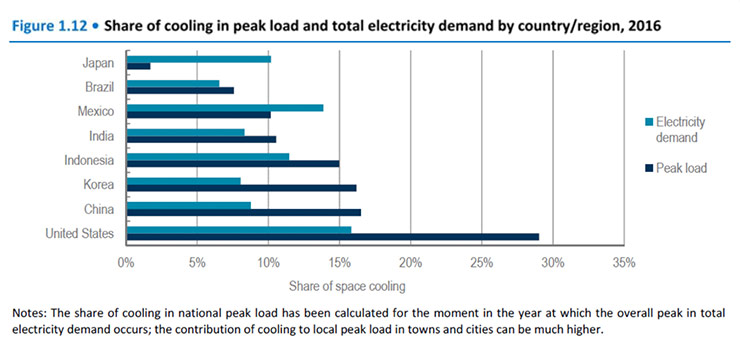

In 2016, air conditioning accounted for around 14% of peak electricity demand worldwide. This figure can be as high as 30% in certain countries, such as the US. This dramatically affects the stability of electricity systems and supply networks.

Cooling contributes significantly to electricity demand, particularly during peaks (source: International Energy Agency)

Current electricity grids will no longer be able to produce sufficient energy needed to meet requirements during peaks in demand. This may lead to unexpected brownouts and power outages. Additional electricity production capacity will therefore be required. However, constructing electricity generation assets purely for peak energy needs results in spending billions of dollars on for mere hours of a year.

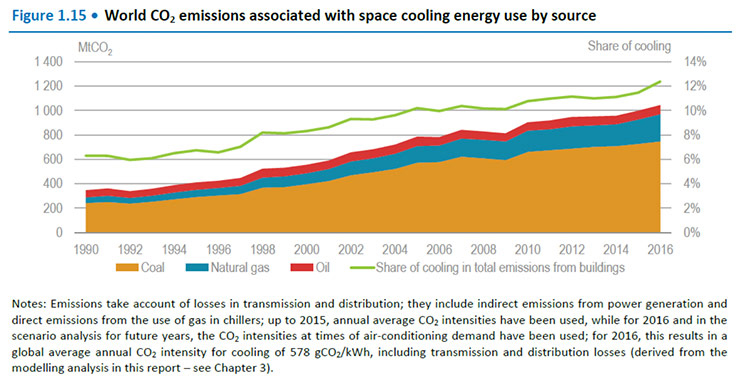

Emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other pollutants such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen also have a significant impact. As an example, CO2 emissions caused by air conditioning have tripled since 1990, reaching 1,135 million metric tons, or the equivalent of the entire CO2 emissions of Japan!

CO2 emissions associated with air-conditioned buildings tripled between 1990 and 2016 (source: International Energy Agency)

The solutions? First off, an effective shell!

Given the global increase in temperature, growth in urbanization and aging population, as well as economic and population growth in developing countries such as India, China, Brazil and Indonesia, the demand for cooling is sure to keep rising significantly in the decades to come.

To slow this trend and limit the impact on energy demand and the environment, the following solutions could be considered:

- Making air-conditioning systems more energy efficient: this would cut the rise in energy consumption linked to cooling by nearly half

- Developing renewable energy, particularly solar power

- Facilitating the adoption of energy storage systems which can reduce peak demand

- Using passive or ultra-low consuming HVAC technologies such as chilled beams or radiant cooling systems

- Improving the energy performance of building shells

The latter approach could contribute to even bigger energy savings in the long term. After all, the ‘best’ energy is the kind we don’t consume at all! If we design buildings with well-chosen materials and a shell that adapts to weather conditions, facilitating good natural ventilation, filtering heat when necessary and providing natural light, then cooling requirements and associated energy consumption can be reduced significantly without compromising the comfort of occupants.

IATA executive office in Switzerland: after its skylight was replaced with more effective, dynamic glazing, the need for air conditioning has been reduced by 60%

Furthermore, the installation of air conditioners makes a major contribution to the urban heat island effect, as well as being one of its by-products. In fact, cooling a space requires heat to be evacuated outside the buildings. It is estimated that air conditioning may cause a temperature increase of over 1°C in certain cities. Yet the higher outdoor temperatures rise, the greater the demand for cooling and air conditioning, and the more heat is sent back outside – so we find ourselves in a vicious cycle. Another good reason, then, to focus first of all on a good shell design.

Better management of demand thanks to smart buildings and grids

The advent of smart buildings, equipped with smart systems and sensors capable of measuring and anticipating temperature, sunshine, light and occupation levels, and controlling windows, ventilation, air conditioning etc. at appropriate times, could help improve the management of cooling demand. On the neighborhood or town scale, the proliferation of ‘smart grid’ systems will also allow the means of energy production, including renewable energy, to be distributed more effectively, and the most extreme peaks in consumption to be addressed. We will return to this subject in more detail in future articles.

- The 2018 Global Status Report – Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction, Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, 2018

- The Future of Cooling – Opportunities for energy-efficient air conditioning, International Energy Agency, 2018