The first mention of Tudor dates back to the year 1926, when Hans Wilsdorf first had the trademark ‘The Tudor’ registered. Six years later, the name would start to appear on several watches. Then, in 1936, Wilsdorf had the actual brand ‘The Tudor’ transferred over to himself. As an Anglophile and eventually a British citizen, he proudly placed the historic Tudor rose and shield on several watches, which, following the 15th century wars, served as a strong symbol of unity. It wasn’t until a year after the Second World War, in 1946, that Wilsdorf determined to give Tudor its own identity once and for all, promptly announcing the founding of ‘Montres Tudor SA’ in 1946.

Tudor movements – predestined to be sourced elsewhere?

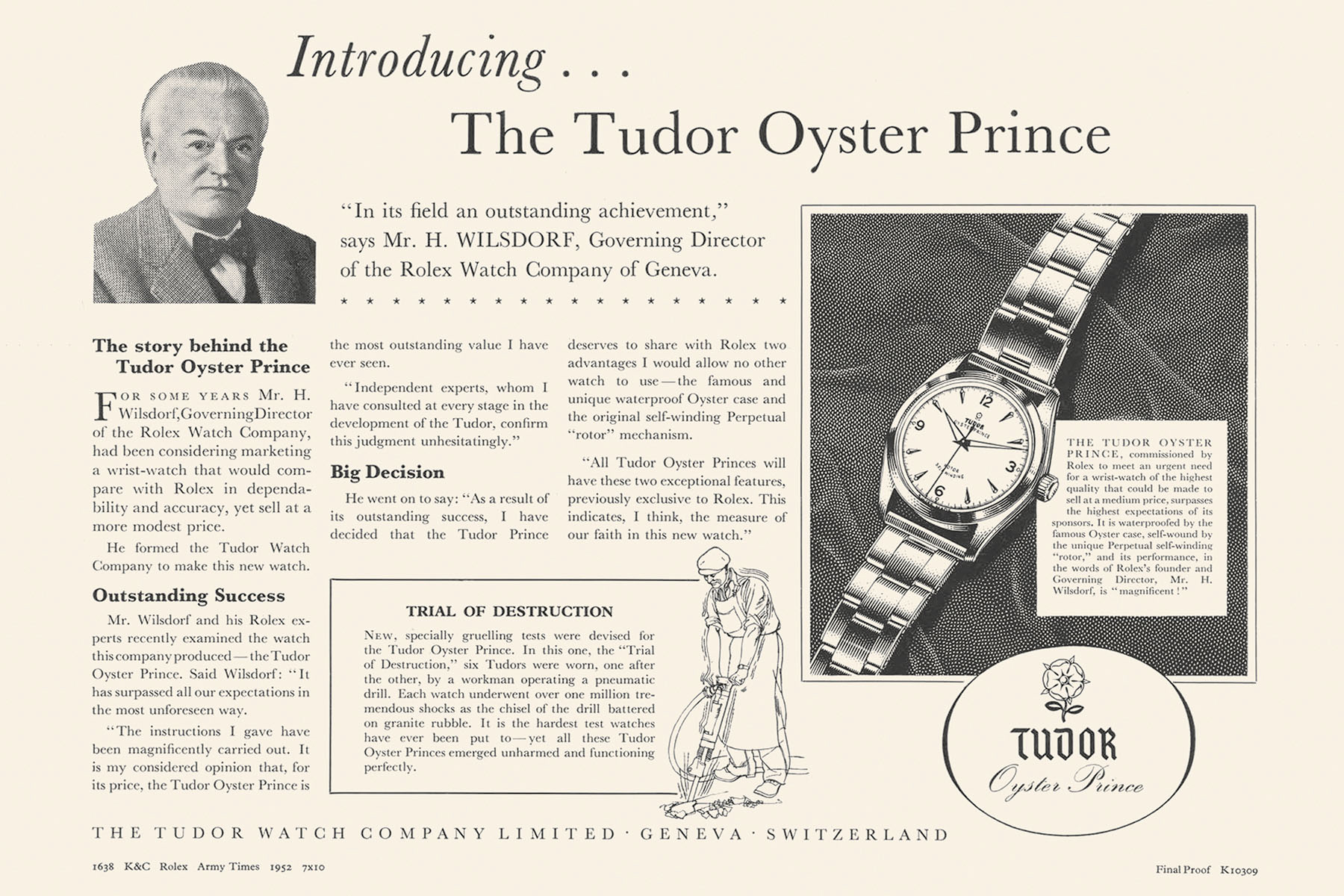

In 1952, Wilsdorf declared that Rolex’s new sister company, destined to sell timepieces ‘at a more modest price than our Rolex watches, and yet one that would attain the standards of dependability for which Rolex are famous’ would use the ‘waterproof Oyster case and the original self-winding Perpetual ‘rotor’ mechanism’ for its Tudor Oyster Prince.

Arguably setting the tone for the future, Tudor would continue to use external watch movements for decades to come – quality movements, but external ones nonetheless. Early chronograph movements were often Valjoux, for example, while Tudor’s ‘Submariners’ (destined to evolve into the Black Bay) favoured the likes of Fleurier’s excellent calibre 360 and later, ETA movements such as the calibre 2483. The external sourcing of base movements remained the status quo up until 2015, when Tudor announced its first in-house mechanical calibre.

The North Flag was the first Tudor model to be fitted with an in-house movement, calibre MT5621

Defying the odds

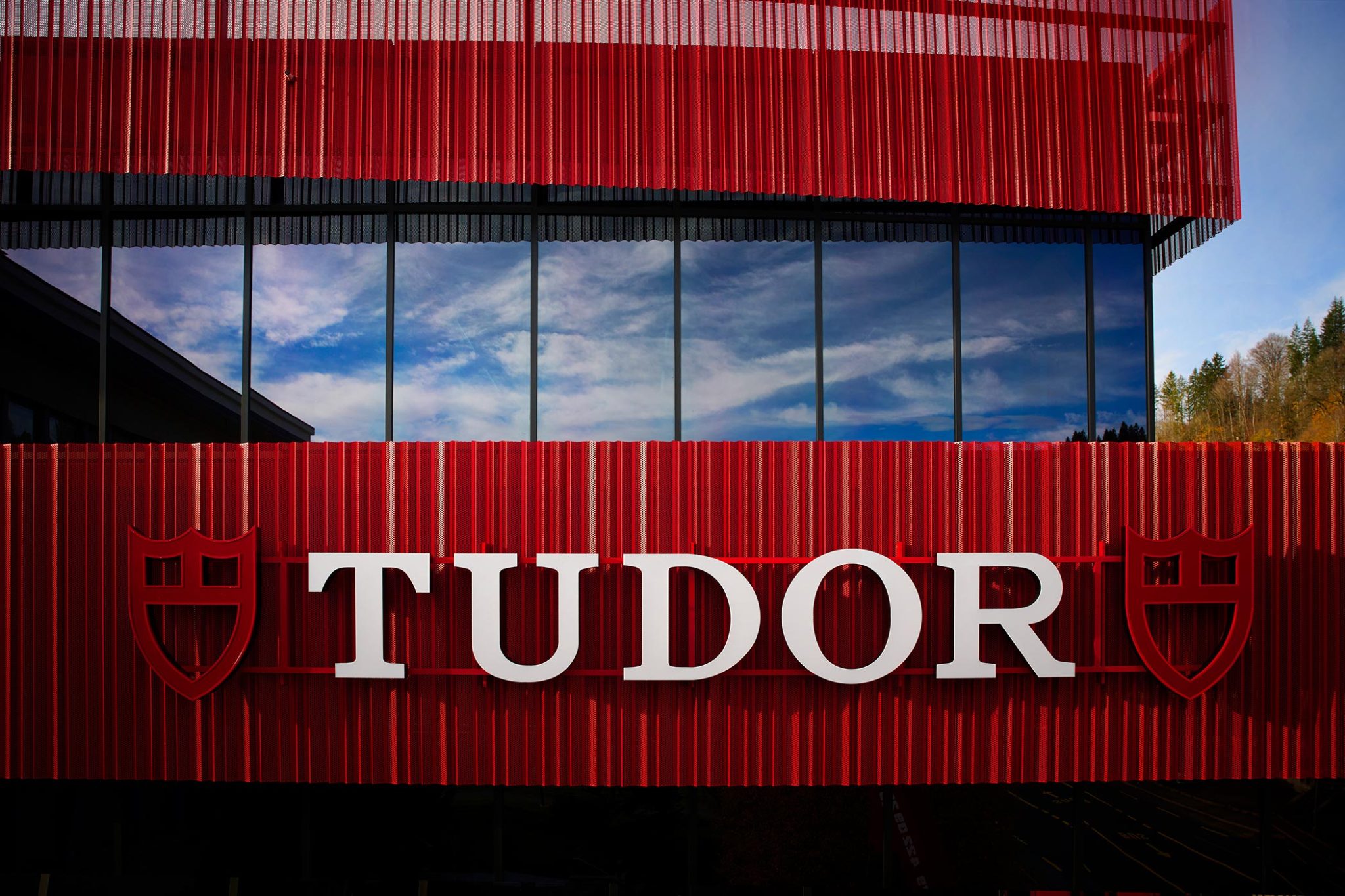

Yet today, a mere eight years later, here we are – standing awe-struck in front of a brand-new Tudor manufacture. As the first industrial facility fully dedicated to the company’s watchmaking in its century-old history, this contemporary Tudor-red structure perching on the Bied river in Le Locle is now the most important building for the watchmaking company. And who better to introduce us to the manufacture than esteemed Tudor frontman and Head of Public Relations, Christophe Chevalier?

‘What you will see here is the Tudor way of doing things,’ he begins. ‘We want to optimise everything as much as possible. Our whole organisation is prepared and deployed so that we can make this happen. What we do here is bring the traditional, manual know-how of the watchmaker together with the absolute best in production management technology.’

Constructing the manufacture

With construction beginning in 2018 and completed by 2021, building this vast and vital new building was a fairly quick turn-around. The decision to build a new manufacture was largely a practical one; Rolex SA already owned the land, and it brought Tudor, which has its headquarters in Geneva, closer to its suppliers in the Jura mountains. Chevalier elaborates: ‘The Jura mountains are also where you can find watch specialists, those in logistics – and this is less easy to find in Geneva.’ Musing for a moment, he adds flippantly, ‘You’re more likely to find bankers in Geneva these days.’

Le Locle, Switzerland

Perhaps ironically given Tudor first gained traction for its use of the waterproof Oyster case, Tudor found to its chagrin that the building needed water-proofing, too. Built beside a river, architects were presented with a challenge due to the extremely wet ground. Therefore, 330 thirty-metre concrete pillars had to be drilled onto a lower-level bedrock underneath the foundations, anchoring the manufacture to the earth. Throughout the construction process, the entire structure also had to be water- and weather-proofed.

Credit © TUDOR Manufacture Book

Architecture

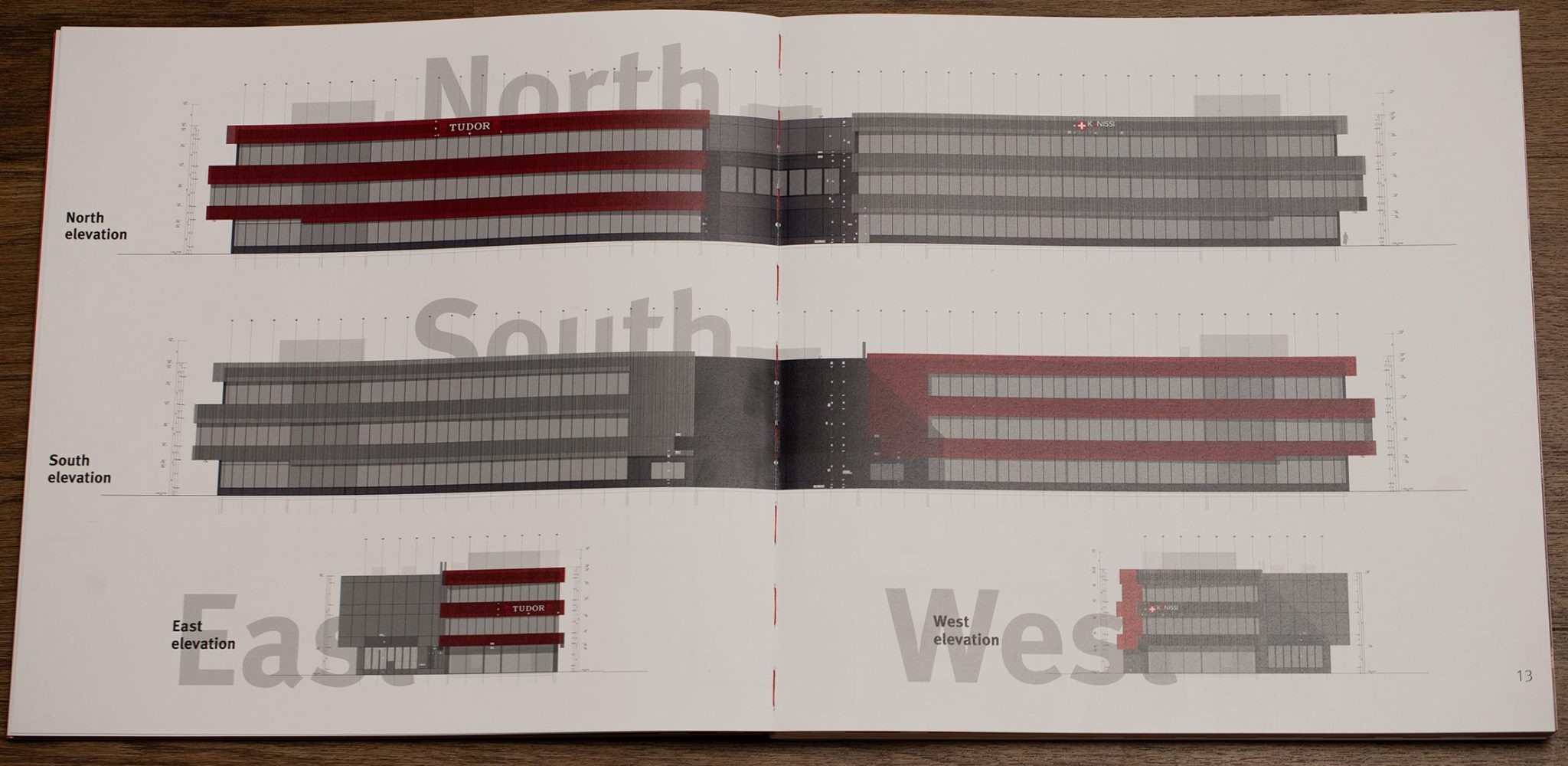

Spanning over 5,500 square metres and four floors – ‘room for proper work’ a proud Chevalier points out – the Tudor manufacture attaches to the Kenissi manufacture, which Tudor founded a year after introducing its first in-house calibre (but more on that later). While the Tudor half to the north is coloured in unmistakable Tudor red, the Kenissi half to the south has a subtler grey tone. Both sides randomly stack hundreds of aluminium panels next to each other, creating a slightly artistic look that reminds me of a modern art museum.

Credit © TUDOR Manufacture Book

These aluminium panels are broken up by large rows of windows, allowing light to flow into the manufacture. Not too much light, though: these special panes are made of ‘Sage Glass’, a special glass that innovatively adapts in order to regulate how much light may be transmitted into the manufacture. Keeping sustainability in mind, the glass also uses light transmission to regulate energy consumption. Much of the building’s energy, incidentally, comes from the 442 solar panels sitting on the roof. That’s not the only way that the building’s design aids watchmakers; it is also home to a special built-in system that eliminates dust as well as maintaining a consistent pressure.

Throughout the manufacture, designers stick to a minimalist industrial aesthetic, including in the reception area. Red and grey are the overriding colours of the furniture. It creates an edgy yet serene ambiance throughout the manufacture. In many ways, the interior design’s simplicity matches well to Tudor’s philosophy. ‘We’re not a rustic workshop doing every bevel by hand’, Chevalier reminds us. ‘We’re producing a high quality, robust traditional Swiss watch that is also very well priced. Everything you see here is geared towards fulfilling that mission.’

The watchmaking departments

The serenity of the interior carries through into the various departments of the manufacture where Tudor’s workforce diligently produces its references. Tudor currently has around 700 references in its portfolio. While the majority are now being produced on-site in Le Locle, around ten percent continue to be produced in Geneva. ‘A full assembly operation from one place to another takes time,’ explains Chevalier. ‘It will take us several months.’

Kenissi manufacture

Now would be the time to bring in Kenissi, home to the manufacture’s assembly floor. Kenissi’s story stems back to 2010, when Tudor first launched its ambitious bid to create a highly robust, reliable in-house movement. By 2015, their dreams became reality with the introduction of the North Flag. The model’s sapphire crystal caseback provided a glimpse of what fans of the brand had long been waiting for: the MT5621, the first ever movement to be developed and produced by Tudor internally. Notably, this first in-house calibre integrated a power reserve indicator, although this was removed from its successor.

Kenissi was created by Tudor a year later in 2016, with the extra production arm also creating calibres for external clients including Breitling, Chanel (which owns 20 percent of Kenissi), Norqain, Tag Heuer, and Bell & Ross. This was possible because Kenissi, unlike Tudor itself, is not part of the Hans Wilsdorf foundation; obviously, Rolex would never allow for its innovations to be made available to external manufactures. That said, while Kenissi’s third-party clients may order minor changes such as decoration or oscillating weight design, the basic architecture of the movements remain the same – and no other brand is allowed to make use of the Spiromax, a patented silicon hairspring reserved solely for Patek Philippe, the Swatch Group, Rolex and its sibling Tudor.

The assembly floor

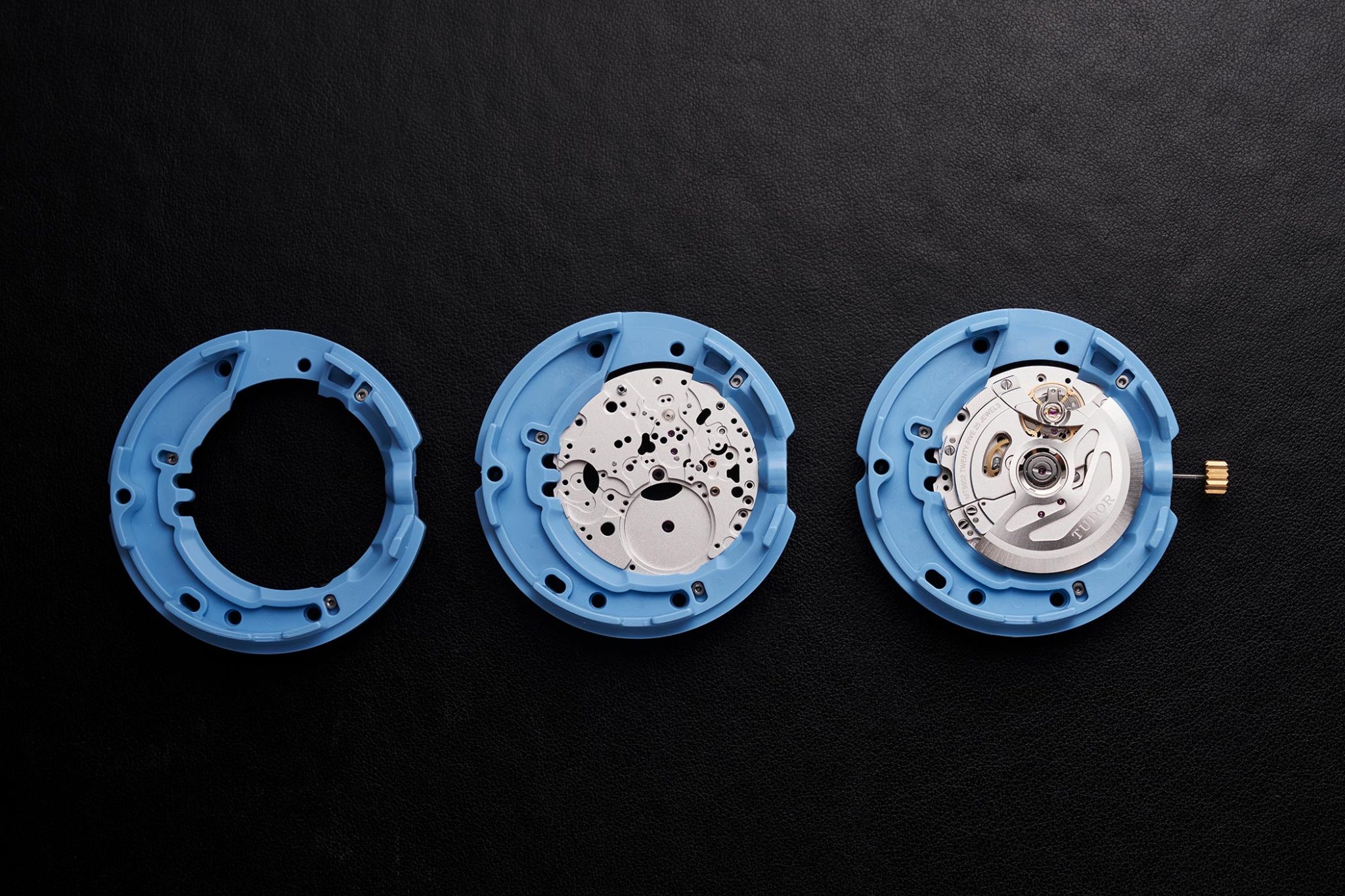

Today, the Kenissi manufacture is home to an assembly floor where its high-quality movements are put together by hand. The watchmakers in this facility – interestingly consisting mainly of women – are dressed in bright white lab coats. Another visitor comments on this unusual gender disparity, to which we are told that women’s dexterity often proves beneficial in this department. The watchmakers here work on three main customisable automatic movements: the MT52 with 50-hour power reserve for its smaller watches, alongside the mid-size MT54 and the large MT56 with 70-hour power reserves. Watchmakers can integrate other functions such as GMT, calendar, and power reserve indicators – although a chronograph is yet to join this central repertoire. Rather, Tudor’s main chronograph movement is derived from the Breitling B01 – given in return, it is believed, for Kenissi’s supplying of three-hand movements to Breitling’s Super-Ocean Heritage calibre B20 several years ago.

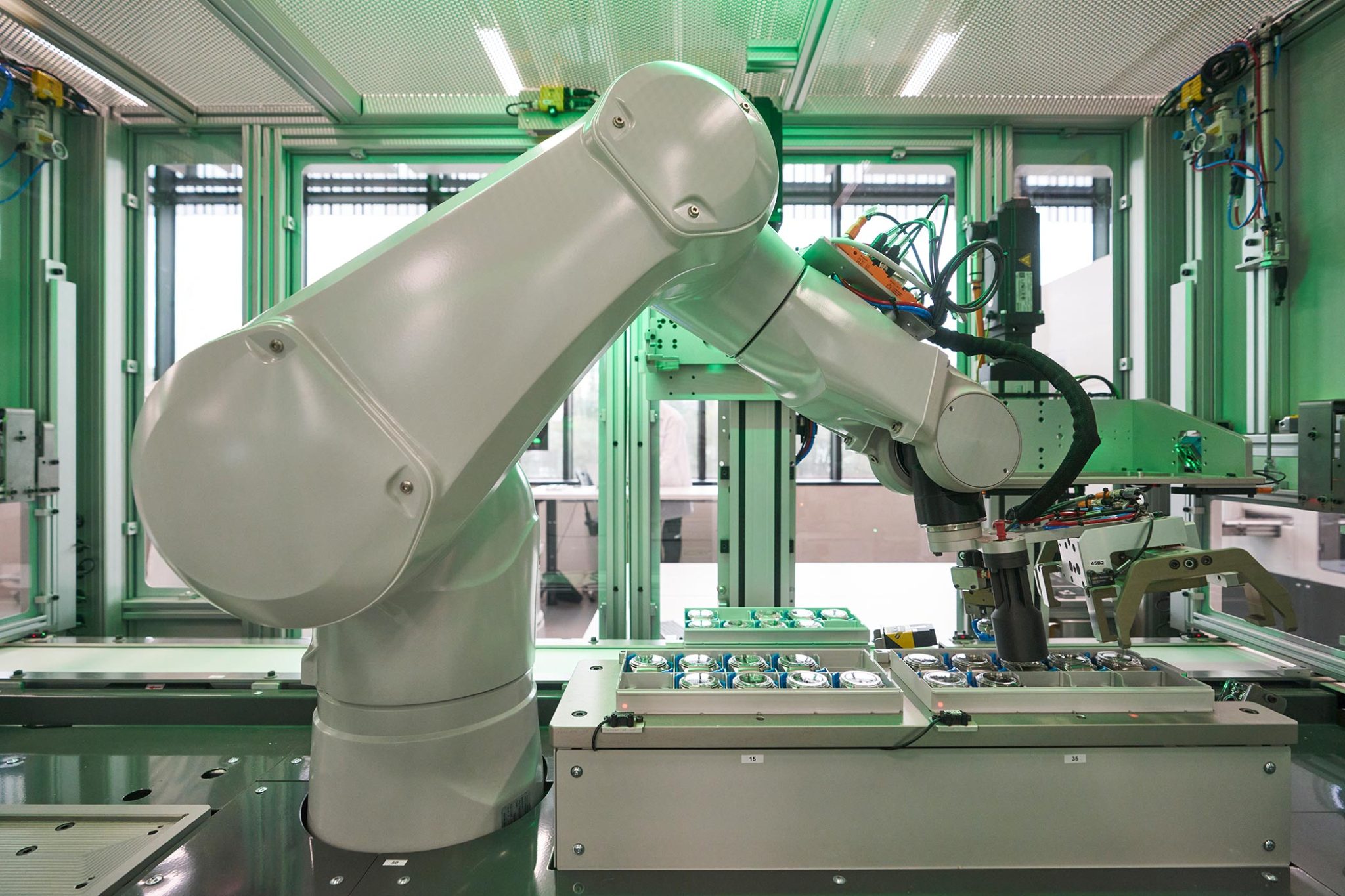

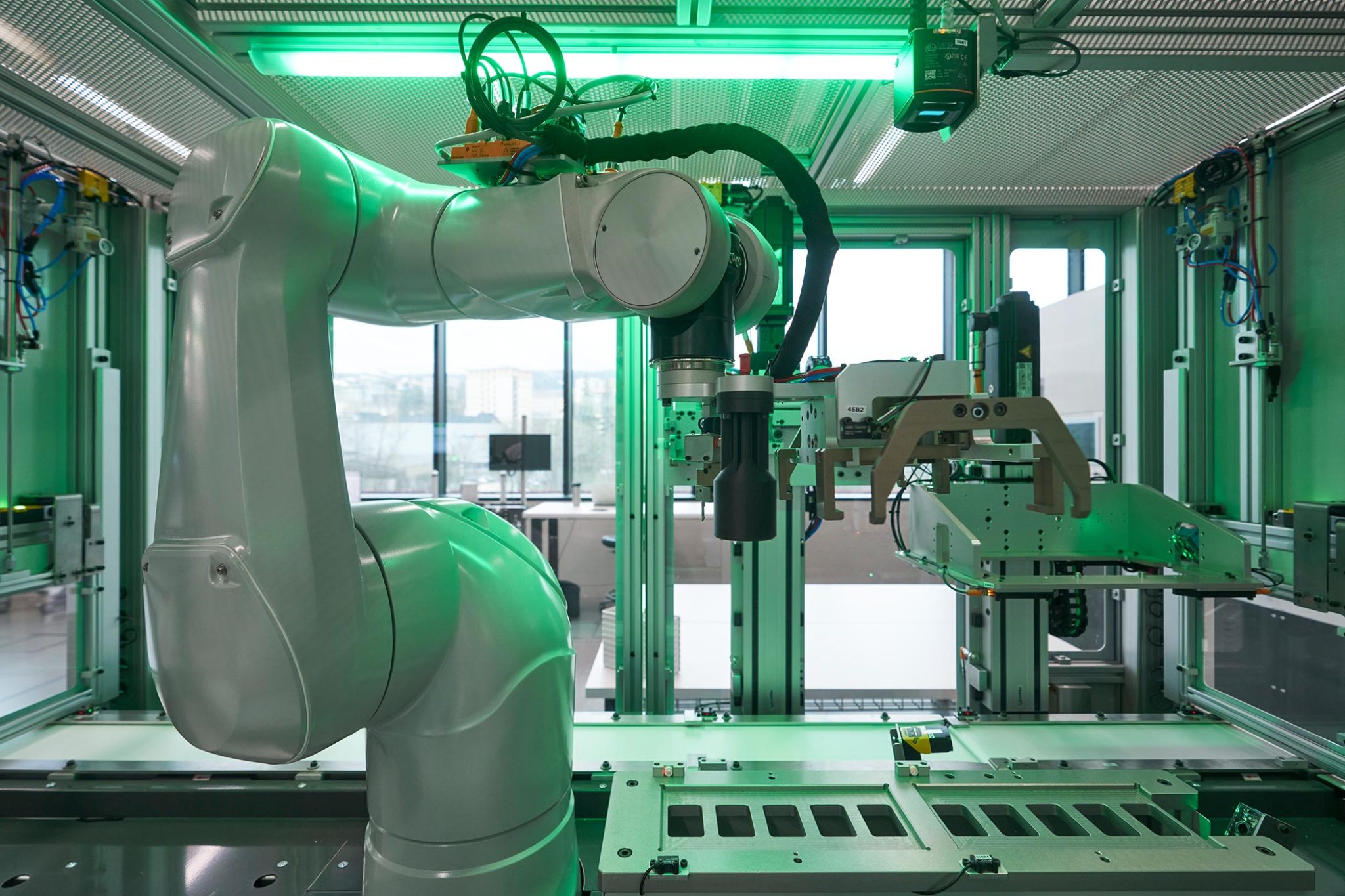

This workshop is home to Tudor’s most skilled and experienced watchmakers, who assemble the movements entirely by hand. An organised assembly line efficiently provides the watchmakers with the right component at the right time in the right position. Certain repetitive operations such as lubrication clearance measurement and chronometry testing is entirely robotised, relieving the watchmakers of unnecessarily time-consuming tasks – but again, we can take a look at this towards the end of our virtual tour.

Tudor also exploits technology in order to achieve not only high standards and efficiency, but also absolute traceability in its watches. Thus, the base plate of each new piece is given a plastic insert containing a ‘RFID tag’. This tag guarantees the correct routing throughout the whole assembly process. Furthermore, it allows Tudor to collect the measurement data and assembly data throughout the whole assembly process. As a result, 100 percent of every single watch’s assembly process can be traced.

Once these base movements have been built, an auxiliary movement, equipped with a dial and hands, are shipped off to the Swiss Official Chronometer Testing Institute. Here, each movement is tested for about three weeks, after which it may obtain a COSC certification.

Tudor manufacture

Final assembly

Following their return, the COSC-certified movements are reinserted to the line for the final assembly step, thus becoming fully fledged in-house automatic movements. The space dedicated to the final assembly of Tudor watches, a master watchmaker and quality specialist informs us, spreads across 560 square metres. As mentioned, Tudor take no risks with dust: the air here is renewed 3.5 times per hour. This final area is usually difficult to obtain access to, and we must past through airlocks to enter.

The watchmakers on this floor are versatile, says our guide, being trained to master and work on any of the 700 references in the Tudor catalogue. Different benches are ergonomically organised to provide space for different purposes: the first, for example, is dial fitting: the last couple of benches are for case fitting. Each of these benches compose a so-called ‘cell’ of watchmakers, always consisting of the same team members. The idea behind this is to improve team spirit, as well as efficiency – the latter in particular being a buzzword at Tudor. After a self-check by watchmakers at every step, the watches undergo a final quality check under the watchful eyes of a master watchmaker. If a mistake is found, the watch will be returned to the person who worked on that particular operation – who is conveniently easy to identify thanks to the aforementioned RFID tag on the base plate.

The testing floor

Up on the second level, we encounter Tudor’s testing floor, where the horology house uses a fully automated autonomous system that runs 24/7 to check its watches conform to METAS and PTC protocols. Robots roam around the floor, transporting the watches from A to B. To give an idea of the scale of what is happening here: the Le Locle manufacture is home to around 46 metric tons of super high technology machinery.

Alongside variable temperature and position watch stockers, the timepieces on this floor also undergo water resistance, magnetic influence (to 15,000 gauss) and precision tests. Typical Tudor calibres shouldn’t deviate more than -2 to +4 seconds per day, while its METAS-certified master chronometer calibre, namely the MT5602-1U found in the Black Bay Ceramic, may deviate between 0 to +5 seconds per day. Not for long, though: the new manufacture hopes to soon METAS-certify all of its in-house movements. Despite learning that 90 percent of the watches being produced on-site at the new Le Locle manufacture, we are informed that 100 percent of its watches are tested here for performance.

Component check, bracelet fitting, and engraving

When components arrive from Tudor’s network of nearby suppliers, batches of dials, cases, and bracelets are scrutinised to ensure that they meet Tudor’s inevitably high standards. Once the components have been approved, they’re returned to the manufacture’s colossal automated stock, where they can be taken up by watchmakers.

On this same floor, straps and bracelets are manually fitted to the watches – the final step in a watch’s manufacturing journey. In the age of quick-change, tool-free bracelets, one might underestimate how meticulously employees in this department work. A simple slip, one employee explains, could damage the case, comprising the hours of work put into the timepiece by its watchmakers. Thus, one single bracelet-fitting expert educates all of the employees in this department.

Finally, this floor is also used for the custom engraving – e.g. initials or logos for special series, such as pieces for the French Navy. No doubt David Beckham’s bronze Tudor Black Bay Pro has also passed through here. While retailers can request big orders of engraved watches directly to Tudor, clients must go through a retailer to make an engraving request. In this area, technology is the favoured tool, with engravings being neatly completed using a laser rather than by hand. Interestingly, custom engravings aren’t only reserved for cases, but are also occasionally possible for dials.

The manufacture’s pride and joy:

the automated stock system

Finally, Tudor keep automated stock in the heart of the building. Here, the manufacture closely guards its components, stocks, as well as fully assembled watches ready to be sent out to one of the watchmaker’s 1,700 points of sale. It is the only area off-access to press photographers; most visitors will never make it down here. This is Tudor’s cutting-edge solution for product management, with only its sibling manufacture Rolex also using a system like this. The concept behind the system is to make all watches and components available to watchmaker in the most efficient way possible. This is achieved through a vast, fully automated network of watch trays.

Each workshop has its own delivery station. A watchmaker can simply order the parts, which will then make its way to the requested place of delivery. The system will also usually be aware of what and when certain parts will be required by the watchmaker, thus ensuring employees are fully equipped with the necessary components at all times. Genius.

The system comes chock-full of high-tech features to be marvelled at by those lucky enough to see it, such as the robotic hands that swiftly manage order preparation. ‘The assembly and fine-tuning of this conveyor system was one of the most complex and time-consuming operations of the building technology part during the construction,’ our guide informs us with unbridled pride. The stock system is the crowning glory of a manufacture whose aspiration is to bring together the perfect marriage of human talent and high technology – and succeeds.

A new era awaits Tudor

When we take into account Tudor’s past – not least its incredibly recent move to in-house manufacturing – it is clear that a new era awaits the horology house. The fledgling Rolex sibling flew the nest a long time ago, with its brand DNA standing strong for several years now. It’s also a well-established collector’s brand, with vintage models offering a myriad of intriguing and diverse external calibres carrying their own stories and associations – but now, future stories of Tudor watches will belong to Tudor alone. The brand has well and truly gained its independence in every sense.

Of course, there will be those who challenge the role of Kenissi – but surely the very location of Kenissi, now physically joined at the hip to Tudor, can provide a clear answer to critics. Tudor has a new home – and there’s no doubt that Hans Wilsdorf’s dream of reliable and robust watches will be continue to be fulfilled from within this bright red building in Le Locle.